So why was a lighthouse built here at this inlet in 1835 and another, a second one, in 1887? Didn’t the 1835 fiasco prove, once and for all, the futility of building a light tower here in sand, on a dangerous and unpredictable inlet, out on nowheresville’s coast? Or did things or conditions change so much, that even with all the problems associated with building and maintaining the 1835 station, a light here was critically strategic for coastal navigation by the 1880’s?

Both Were Strategic.

A lot happened in fifty-two years in the United States, and particularly in, about, and to Florida. Here, “once bitten, twice shy,” didn’t hold for Mosquito/Ponce Inlet and the essential placement of another, larger navigational aid at this inlet. In 1835, the livelihood and success of pioneer planters trying to make a go here, depended on placing a tower and lightstation to mark the inlet. By 1884, it wasn’t just the inlet at stake. There were more significant, urgent ones. The 1835 effort was of benefit locally. The second, lit on November 1, 1887, was of enormous benefit nationally.

In 1835, the south shore 45-foot light tower and keeper’s residence was built to light and mark the inlet to encourage the growth of trade and commerce into the inlet, and to assist in growing its environs. It certainly made sense that local petitioners drew up, signed and advocated for the 1834 lighthouse solicitation to the Federal Government. They knew, firsthand, the need. Yes, there were bigger dreamers who regarded the inlet and the river it flows to and from, as a future, grand harbor which would robustly kindle more trade and traffic in the area. Florida isn’t a state yet, and this natural area they thought had the potential to be a major harbor along the coast. Those petitioners argued ”…the culture of Sugar…it may fairly presumed, that a Vast business will ere long be carried out on in that article in addition to which Large Quantities of Live Oak timber, so essential in the construction of our Navy, grow in this section of the Territory all of which must pass over the Musquito Bar…during the last fifteen months about Thirty sail of Vessels (principally Brigs and large Schooners) have passed over this bar.”

The 1835 lighthouse was built with the keeper’s residence, and a local man, William Williams, the son of one of those local planters, was appointed keeper. The construction of the station itself, went smoothly for a Winslow Lewis project. Despite its design, lack of an adequate foundation (if any at all), insufficient height at its chosen location – on a sandy dune, too far back from the inlet’s mouth, too close to the waters of the inlet, it was built. Oh, and one more thing. The oil for its reflective lamps had not yet been ordered or delivered.

The litany above, poor structural decisions before and during its construction, and violent storms almost immediately after, contributed to damaging and destroying the 1835 tower. Let’s also not forget, the beginnings of The Second Seminole War, with an attack by a Seminole War Party directed at the tower itself, burning the wooden door and smashing all the glass. It certainly contributed to its wretched condition. In normal times, repair of the isolated tower would certainly take awhile, but what really stalled any attempt to repair the tilting tower was that of necessity, all settlers and potential laborers fled the area to the relative safety of St. Augustine, due to fear of the continuance of Seminole attacks. That historic series of storms that fall and winter and the poor build saw the tower finally fall completely into the inlet in April of 1836, after months of instability and inaction on repair.

Bolder Sand

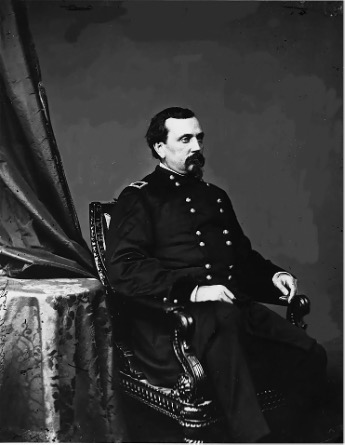

The 1887 light was also raised at the same inlet, but this time it was erected on the North shore. (“Here there was bolder sand,” declared Engineer and US Army General Orville Babcock. While not officially an engineering term, we understand this “bolder” describes firmer sand.)* This light was not erected to mark entrance and assist navigation of the inlet as such, and while it did so, that was no longer its primary purpose. Looking at a map, and listening to the complains of coastal captains, there was too much shoreline distance, (a ninety-three-mile gap), between the North standing navigational aid, a lighthouse tower at St. Augustine, and the primary navigational aid to the South, the Cape Canaveral light tower. In lighthouse parlance, this gap would be called a “dark coast” – that had to be lit. Theoretically, the maxim was that along a coast, a ship should see a light over the bow of their ship showing from the tower they were approaching, while still seeing being able to see a light over the stern of the last tower they passed.

The best bet was to scout the inlet and its area again, and chose a place with that “bolder” sand to construct a -so-many-foot-tall tower, further back from the water. And they did. Also, while the inlet area itself was not, this time, the primary target to mark, but was a very convenient place to bring building materials into. Finally, it was on target to be about half-way between the St. Augustine and Canaveral towers, so it pretty much filled that gap and lighted that “dark” coast.

The comparison between the two light towers, the 1835 tower and the 1887 tower, who built them, and how they were built, is striking.

While some of the early towers, built in the same fashion to our poorly constructed and poorly located 1835 tower have been successful, and some even still serve today, (see Florida’s Amelia Island, and Maine’s Pemaquid Point lighthouses as examples), the second Mosquito/now Ponce Inlet tower had professionally trained Army Corp of Topographical Engineering officers, both General Orville Babcock and Major Jared Smith, who both had extensive engineering training and experience, and about twenty prior, successful and well-built brick giant lighthouse plans to compare with their own.

It is also fair to say that the Mosquito/Ponce is the perfect American brick giant lighthouse, because all the mistakes were already made in the long line of those brick giant towers built before Florida’s Jupiter Inlet, and the ABC brick giant lights of New Jersey, Absecon, Barnegat and Cape May. All four have the fingerprints of General George Gordon Meade, the Father of the Brick Giant Lighthouses, all over them.

As an interesting note, only one of the “brick giants” has been lost. Shinnecock Bay Lighthouse, erected in 1858, on Long Island, New York, was 168 feet tall and helped fill the sixty-nine-mile gap between the lighthouses of brick giant Fire Island and early Federal Montauk Point Lighthouse. (Sounds very much like the 1887 Mosquito/Ponce Inlet Lighthouse being needed because of the gap between St. Augustine and Cape Canaveral.)

A metal tower at Shinnecock Bay was erected in 1931 to replace the brick giant Shinnecock Light, however a 1939 hurricane took that metal tower out. The storm did not faze the brick giant. After the hurricane, the Coast Guard still felt Shinnecock was unstable, and despite an extensive and positive engineering inspection which concluded the brick tower as “safe and stable,” the Coast Guard pursued its plans and took the tower down.