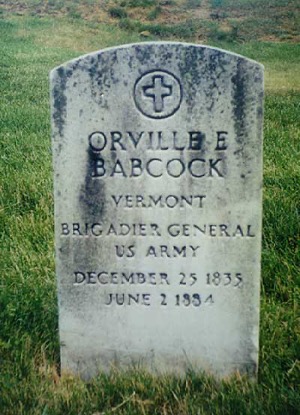

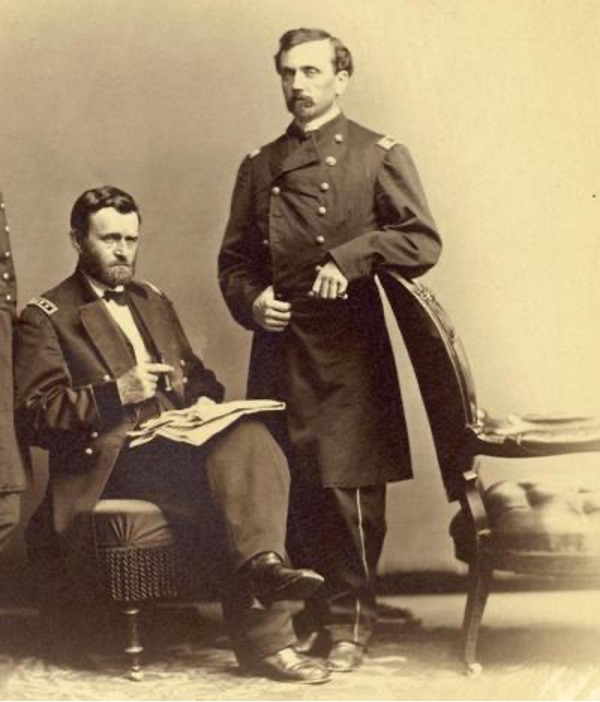

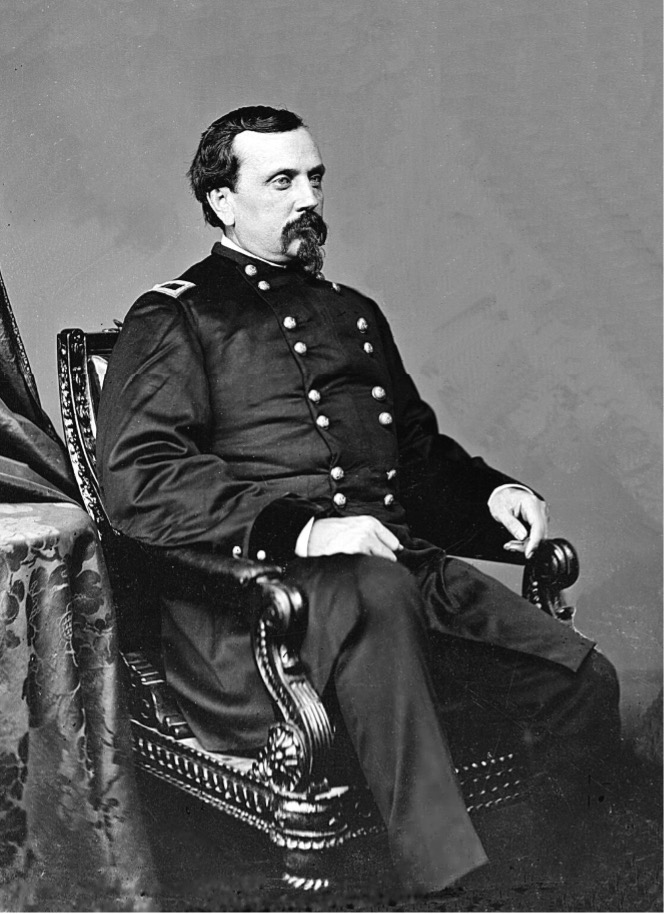

The late spring of 1884 was equally star-crossed for both former U.S. president, Ulysses S. Grant, and his friend, fellow-officer, advisor and subordinate, Orville Elias Babcock. General Babcock was Grant’s Civil War chief aide, later presidential secretary, and if there was such an office then, White House Chief of Staff. Babcock is better known to us in the lighthouse community as the original supervising engineer of the Mosquito (now) Ponce Inlet Lighthouse. While William McFeely, a Pulitzer Prize winning author of a 1981 somewhat critical presidential profile called, GRANT A BIOGRAPHY, dismissingly portrayed Babcock as, “an unexceptional man,” he also acknowledged Babcock, as did Ron Chernow, author of the best-selling GRANT in 2017, as Grant’s closest friend, and his sole confidante during his presidency.

In May of 1884, Grant would learn he was bankrupt and essentially penniless. A month after this bad news, he was diagnosed with advanced throat cancer, a death sentence at that time. Grant immediately began to write an autobiography, not just to preserve his legacy, but to erase the debt and leave his family in more favorable financial circumstances. On some days he completed fifty pages in his race against time. His legendary photographic memory did not fail him in this task, as it seemingly did during the legal battles he encountered in his White House years. Grant died a year later, less than five days after finishing his book. The memoir, written with the encouragement of Mark Twain and Twain’s publisher, was itself a best seller and helped to sustain his family after his death on July 23, 1885. McFeeley’s book, generally seen as an unsympathetic appraisal of Grant as a general and as president, did present Grant’s memoirs as, “the finest that have ever been written by a president, remarkable for their clarity, conciseness, and classic prose.” The two-volume account only covers the period up to the end of the Civil War, perhaps deliberately by Grant to end his story with his greatest achievements, and thus to avoid his presidency.

President Grant – A Promise of Peace, Prosperity and Progress

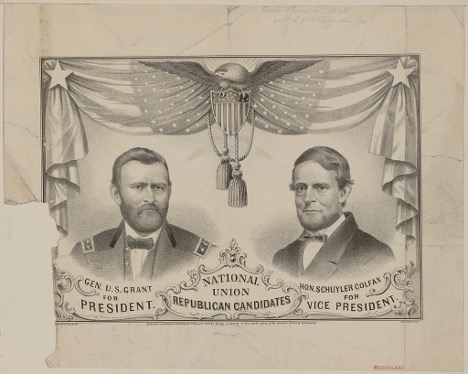

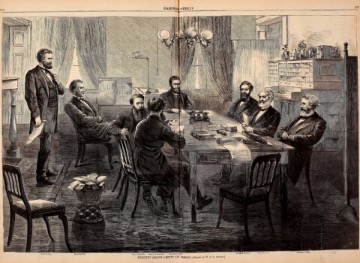

In November of 1868, General U.S. Grant won the election against Democratic opponent Horatio Seymour with the slogan: “Let Us Have Peace.” He won the presidency as a conquering hero. Unlike much of the South, the North, victorious in the Civil War was almost unaffected by actual war damage, and frankly enriched by the production of war materials. Grant’s years in office were marked by huge change, reconstruction and transition for the country. The southern states bitterly fought the policies of Reconstruction and civil and voting rights for freed slaves. America began to move westward. Railroads crossed and covered the country and helped to transport goods mass manufactured by new corporations. In turn, those corporations grew more powerful. The need for more workers and more consumers spurred immigration. Cities were growing as political hotbeds, and education, civil service reform, money supply, tariffs, and labor (child and adult) conditions were being debated.

Most scholarly scrutiny maintains that Grant’s administrations were awash in fiscal mismanagement by corrupt associates and cronies, eventually resulting in an economic depression in the middle of his second term. Certainly, scandals overshadowed his many accomplishments. It is agreed that that his military successes did not prepare him fully for the rigors of battle with the politicians of Washington. However, most also agree that Grant vigorously fostered reconstruction in the South, fought the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan, protected civil rights of freemen, championed the Fifteenth Amendment, pursued peace with the Plains Indians, and in a remarkable singular act, appointed the first black man to West Point as a cadet.

The Gilded Age

The period of Grant’s two presidential terms (1869-1877) is also disparagingly interpreted by many historians and pundit-journalists of the times as “The Gilded Age,” a term coined by Twain and co-author Charles Warner, and used as the title of their 1873 satiric novel. Subtitled, A Tale of Today, the book examined the financial instability, moral corruption and chaos of post-Civil War America. The term parodied the period, describing the era as having a glossy patina of gold coating, but concealing underneath something worth very little. It lampoons the period as a time of extravagant plenty for the few, with crushing poverty and child labor for most.

Largely escaping blame for the failings of his subordinates, Grant was – and is still, characterized by most historians as scrupulously trustworthy, incorruptible, and decent, but naïve and dreadfully inept at politics. They opine that he mistakenly surrounded himself with dishonest cabinet members and associates, many of whom were Civil War comrades-in-arms. “Bound with hooks of steel,” was how fellow Civil War General Greenville M. Dodge described Grant’s loyalty to country, God, and his friends. William Tecumseh Sherman said, “I always knew when I was in trouble that Grant was thinking about me and would get me out. And he did. He stood by me when I was crazy and I stood by him when he was drunk; and now, sir, we stand by each other always.” Grant’s “fellow-officer-in-arms loyalty” to friends, subordinates and cabinet members, believing they were incapable of deceit or fraud, set the course for possibly the most corrupt administration in the nation’s history. It is always ironic that Grant ran and won the presidency on a platform of “A Promise of Peace, Prosperity and Progress,” principally built around his moral authority as a war hero.

Despite a seemingly unending series of notorious scandals he was at the heart of, was tried for, or was accused of being involved in, Babcock remained at the White House as private secretary until practically the end of Grant’s presidential tenure. However, researchers do see that in the beginning of the second term, Grant did seem to begin to distance himself from Babcock.

General Babcock Lighthouse Engineer

Almost immediately after leaving Grant and Washington in 1877, Babcock was appointed by the new president, Rutherford B. Hayes, as US Lighthouse Board Inspector and Chief Engineer for the Fifth Lighthouse District. A few years later he also became Engineer for the Sixth District. These areas then covered the Atlantic Coast essentially from the Cape Charles light in Virginia south to the Cape Canaveral Lighthouse in Florida. He also served in that capacity for presidents Garfield and Arthur. And as such, he assumed the role of project designer and administrator for the construction of a major coastal lighthouse needed to mark the almost 100 mile stretch of “dark coast” in that Sixth District between the St. Augustine Lighthouse, lit in 1874, and the Cape Canaveral Lighthouse, lit in 1868. It was in this capacity that he submitted his proposal on February 7, 1883, for purchase of ten acres of land at $400.00 for a First Order Light to be constructed on the north or “bolder” (more substantial) side of the Mosquito Inlet at property then known to Babcock as ‘Point Ponce.’ The land, part of an original Spanish Land Grant, was now owned through inheritance by its current resident, Bartola Pacetti and family. The Pacetti’s were descendants of the 1400 Minorcan and Italian indentured servants who were brought to Florida ninety years before to establish a plantation for growing hemp, indigo and sugarcane along the western shore of the river. The plantation failed, most of the immigrants died, and the rest fled to St. Augustine seeking relief from their servitude. A few, like the Pacetti family, returned and managed to survive in the sparsely settled area. In the 1840’s and 50’s, it is estimated that fewer than one hundred people lived between the inlet and St. Augustine to the north!

At first, Babcock inspected the site of the 1835 Mosquito Inlet lighthouse tower which was built on property on the south side of the inlet, and still owner by the US Government. The south inlet side 45 ft. tower, built by Winslow Lewis, was the victim of poor engineering and vicious storms. It collapsed into the sea even before being lighted. Babcock wisely rejected that side of the inlet. The inlet, notorious for its shifting sandbar, and channels, is still considered one of the most dangerous on the East Coast of the United States.

As a consequence of the tricky and treacherous waters of the inlet, brick was chosen for the building material rather than a skeletal tower. Babcock thought that transporting building materials like brick over the inlet’s bar, in the event of likely ‘gales,’ would be cheaper and easier to replace than losing the more expensive, and sometimes singular, cast pieces of a screwpile tower.

A Busy Engineer and Another Project

One week later on February 16, 1883 Babcock submitted a second proposal to the Lighthouse Bureau, this time for another lighthouse station, this time on Florida’s main water artery, the St. Johns River. Florida and its citrus were discovered and a station was needed to assist and guide the growing steamship traffic at the south entrance to St. John’s largest lake, Lake George, by marking that dangerous bar with a light and fog horn. Not so Herculean a task as a tall, coastal first order light, the screw pile Volusia Bar Light Station was activated with its fourth order fixed Fresnel lens and a fog bell powered by a machine, about a year before the inlet light station was completed.

While the engineering and construction of the Mosquito Inlet Lighthouse followed the principles of design standards for the other “Brick Giants” built in the decades between the 1850’s and the 1880’s, Babcock’s name is on the plans and must be given credit for successfully bringing all of the initial project pieces together before personal misfortune struck.

Calamity at Mosquito Inlet

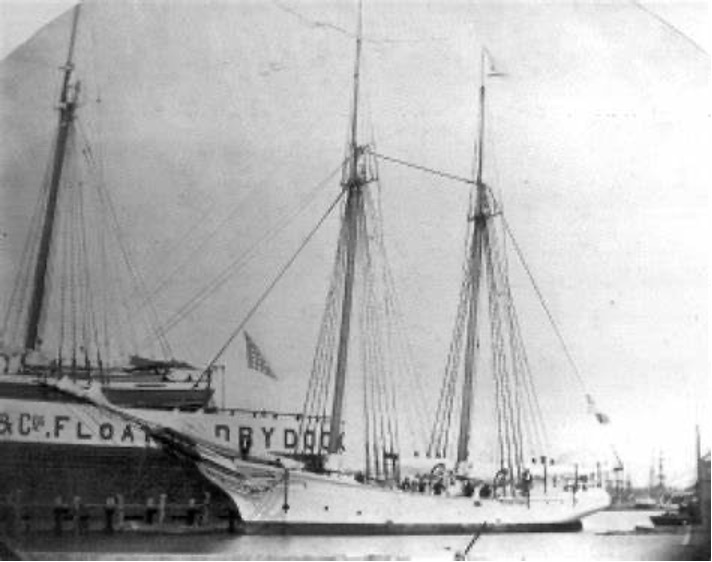

On June 2, 1884, Babcock and several other lighthouse service employees were on the Lighthouse Service tender Pharos, making another trip to the site. In addition to the inspection party, the tender’s cargo hold was heavy with cast iron gallery pieces and stone materials to be delivered to the newly cleared lighthouse location. Pharos was anchored about a mile from the always dangerous Mosquito Inlet Bar.

To make matters worse, a gale had battered the Florida coast for a week. The Pharos captain, his ship weighted down with building supplies, wisely decided not to try to cross the bar. Babcock, not anxious to continue “weathering” the storm on the anchored tender, successfully hailed a whaleboat, a sturdy, maneuverable thirty-foot type of craft with oars, to take him and his associates over the bar to the lighthouse dock. Ironically, Babcock previously recommended on several occasions taking the “inland interior waterways” route to the Halifax River in order to approach the lighthouse site because of the treacherous nature of the bar and the inlet. Running out of luck, Babcock and three other men, two of them Lighthouse Service employees, were killed in the stormy breakers that afternoon. The whaleboat’s steering oar broke, the vessel turned sideways, and the boat swamped and capsized in the wild surf throwing Babcock and the others overboard. Tossed a rope, the dazed Babcock hung on, was lost, and retrieved several times, until he was washed away in the whitecaps. His body was found later on the beach. His remains were returned to Washington and eventually interred at Arlington National Cemetery. He was forty-seven years old.